Flare-On 2022: T8

For T8, I’ll have to first bypass a really long sleep by manipulating the date time on my VM. Then I’ll look at a GET request, and compare it to what’s in a given PCAP. The response doesn’t match the PCAP. The first step is to understand the payload sent, and then to fake a server and send a response to understand how to it is decrypted, and then apply that to the PCAP data.

Challenge

FLARE FACT #823: Studies show that C++ Reversers have fewer friends on average than normal people do. That’s why you’re here, reversing this, instead of with them, because they don’t exist.

We’ve found an unknown executable on one of our hosts. The file has been there for a while, but our networking logs only show suspicious traffic on one day. Can you tell us what happened?

The download contains a 32-bit Windows exe file and a packet capture file:

oxdf@hacky$ file t8.exe

t8.exe: PE32 executable (console) Intel 80386, for MS Windows

oxdf@hacky$ file traffic.pcapng

traffic.pcapng: pcapng capture file - version 1.0

PCAP

The packet capture file has 24 packets making up two TCP streams, each from 192.168.10.15 to port 80 on 13.13.37.33. They are both POST requests, each with a 16-bit base-64 encoded string as the body, and an ASCII base64-encoded string comes back:

One subtle difference to notice here is that the User-Agent string is different between them, the first ending in “11950”, and the later ending in “CLR”.

Run It

Double-clicking the exe opens a window and just hangs. Running it via a terminal shows the same behavior:

Knowing there’s network traffic involved, I’ll run again with Wireshark capturing, but still nothing.

RE

Get Program to Run

Find Sleep

The first thing I’ll need to do is figure out why it isn’t running. In Ghidra, in the Symbol Tree window, under Imports -> KERNEL32.DLL, Sleep is listed. Right clicking and selecting “Show References to” pops a window showing two references:

The latter is just the external address table. Going to the first one, it’s in a function that I’ll name Main (0x404680).

At the top of Main, there’s this loop:

iVar6 = FUN_00404570(_DAT_0045088c,uRam00450890);

while (iVar6 != 0xf) {

Sleep(43200000);

iVar6 = FUN_00404570(_DAT_0045088c,uRam00450890);

}

Until this function returns 0xf (15), it will sleep 4,320,000 ms (12 hours) and try again.

Sleep Calculation

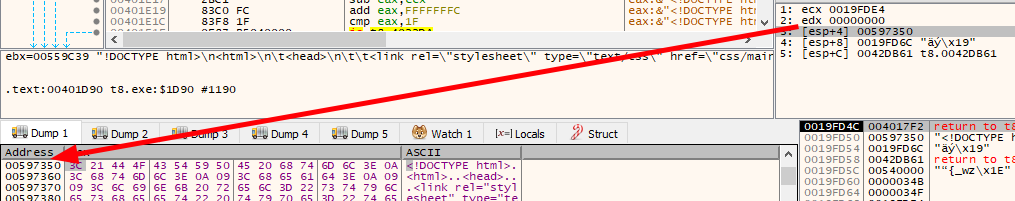

I’ll open t8.exe in x32dbg and go to 0x45088c in the dump window. I’ll right click on the first byte, and create a hardware breakpoint on access to that memory:

Running the program, just after the entrypoint there’s a hit:

There’s a move from the xmm0 register into this address:

This is in a function I’ll name initialize_times (0x401020). The decompilation isn’t very helpful, but there’s clearly a call to GetLocalTime, and then assignment to a bunch of these globals. The SYSTEMTIME struct has a bunch of WORD values (2 bytes), as seen here:

The code then puts pairs into different globals.

Back in the function that determines if there’s a Sleep, takes two inputs, the globals with month and year, as well as day of month and day of week, and does a calculation:

month = month_year >> 0x10;

year = (month_year & 0xffff) - 1;

if (2 < month) {

year = month_year & 0xffff;

}

decade = (int)year / 100;

mod_month = month + 0xc;

if (2 < month) {

mod_month = month;

}

fStack00000010 =

(((float)(((((int)((double)(year + 4716) * 365.25) -

(int)((double)(mod_month + 1) * -30.6001)) + (day_dow >> 0x10) +

((int)(decade + (decade >> 0x1f & 3U)) >> 2)) - decade) + 2) - 1524.5) - 2451550.0

) / 29.53;

fVar1 = FUN_0043c3d0((double)fStack00000010);

fVar1 = _roundf((fStack00000010 - (float)fVar1) * 29.53);

return (int)fVar1;

}

Even without knowing what these are, I could look at some of the constants to make an educated guess. 365.25 is days in a year, 30.6001 is a days per month estimation. It’s calculating some time value/

Bypass Sleep

Rather than reverse these algorithms exactly, I’ll do some experimenting. After disabling the VirtualBox need to set the guest time in VMs, I’ll start playing with different dates in the VM and running to this return to look at the value. One value I’ll discover is 10 Oct 2022 leads to a return of 0xf, which skips the sleep.

Now when I open the program, it hangs for a second, and then goes away. Progress!

Looking in WireShark, I see the same kind of request as above, but with different body and number at the end of the User Agent:

The response is a Flare-On webpage, so clearly different from what was in the PCAP. If I run this a couple more times, the UA number and base64 body change each time, and the response is the same.

Find UA Number

Believing that the UA string number is important (perhaps some kind of key shared with the server), I want to figure out how that is generated. While I won’t end up needing it at all, it helps me to figure out the program in general.

entry

The entry function looks very similar to the function from the previous darn_mice challenge. There’s one part that’s worth understanding here:

__initterm_e and __initterm are functions that will walk a table of function pointers and call each of them successively, from the start address to the end address. Null values are skipped.

These tables look like this:

One of these is where the times were initialized (show above).

The only other call that’s interesting is at the end of the entry function, where it calls the function mentioned earlier, Main:

get_argv();

get_argc();

unaff_ESI = Main();

It gets the command line, but doesn’t use them, and calls Main.

String Generated

Shortly after the sleep loop, there’s a call (0x404839) to a function that takes a global in and returns the string of numbers that ends up in the UA string:

puVar10 = (undefined4 *)FUN_004025b0((undefined2 *)&local_3c,DAT_00450870);

With a breakpoint on this global, it’s also initialized in the intialize_times function. The decompile isn’t great here, but looking in the assembly, it shows that GetLocalTime is called with a pointer to a space on the stack, starting at EBP-20:

00401060 8d 45 e0 LEA EAX=>local_24,[EBP + -0x20]

00401063 50 PUSH EAX

00401064 ff 15 CALL dword ptr [->KERNEL32.DLL::GetLo = 0004f3b6

10 e0

43 00

0040106a 0f b7 MOVZX EAX,word ptr [EBP + local_24[10]]

45 ea

0040106e 8b c8 MOV ECX,EAX

00401070 c1 e1 04 SHL ECX,0x4

00401073 2b c8 SUB ECX,EAX

00401075 0f b7 MOVZX EAX,word ptr [EBP + local_24[12]]

45 ec

00401079 8d 04 88 LEA EAX,[EAX + ECX*0x4]

0040107c 69 c8 IMUL ECX,EAX,0x3e8

e8 03

00 00

00401082 0f b7 MOVZX EAX,word ptr [EBP + local_24[14]]

45 ee

00401086 03 c8 ADD ECX,EAX

00401088 51 PUSH ECX

00401089 e8 87 CALL FUN_00422015 undefined * FUN_004220

0f 02 00

0040108e e8 61 CALL FUN_00421ff4 uint FUN_00421ff4(void)

0f 02 00

It gets the 10th word, shifts it by 4 (which is like multiplying by 16) and then subtracts itself (so now only multiplied by 15). It gets the 12th word, and adds that to the other one times 4 (which was already times 15, so now times 60). This kind of math continues until I get the total milliseconds as:

total_ms = ((min*60) + sec) * 1000 + ms

That value is passed to FUN_00421ff4, which calculates a value:

(((((total_ms) * 343fd) & 0xffffffff) + 0x269ec3) >> 16) & 0x7fff

This is a two byte integer values that it stored in a global value and is the UA string int.

Functions

Capa

Capa is a really neat tool that comes in handy on this one. It will look for functions doing well-known / potentially suspicious things, and call them out. Here, running capa t8.exe -v includes this output:

Now as I come across these, I can verify and easily see what they are, without having to recognize the RC4 or MD5 algorithm myself.

Function Table

There’s a function just before the conversion of the magic number to the string that I’ve named get_function_table (called at 0x4047d6):

function_table = (int *)get_function_table(pvVar5,in_stack_ffffff3c);

This function gets the CClientSock::vftable object and saves a pointer to it:

********************************************

* const CClientSock::vftable *

********************************************

CClientSock::vftable XREF[2]: get_function_table:004

FUN_004035f0:004035f9(

0044b918 f0 35 addr[

40 00

70 37

0044b918 f0 35 40 00addr FUN_004035f0 [0] XREF[2]: get_function_table:004

FUN_004035f0:004035f9(

0044b91c 70 37 40 00addr FUN_00403770 [1]

0044b920 a0 37 40 00addr FUN_004037a0 [2]

0044b924 20 3c 40 00addr FUN_00403c20 [3]

0044b928 e0 3c 40 00addr FUN_00403ce0 [4]

0044b92c d0 36 40 00addr FUN_004036d0 [5]

0044b930 60 38 40 00addr FUN_00403860 [6]

0044b934 70 3d 40 00addr FUN_00403d70 [7]

0044b938 00 42 40 00addr FUN_00404200 [8]

0044b93c f0 43 40 00addr FUN_004043f0 [9]

0044b940 10 39 40 00addr FUN_00403910 [10]

I’ll see these called throughout Main like this:

(**(code **)(*function_table + 4))()

Encryption

With the capa output, I’ll focus on the base-64, MD5, and the two RC4 functions.

Base64

I’ll put breakpoints at both 0x4014c0 and 0x401d90, and run til it hits first 0x4014c0. Ghidra shows this as a __fastcall function, so I’ll set x32dbg to that, but none of the args show anything obvious.

However, on hitting “Run til return”, now EAX is a base64-encoded string:

I can test and confirm that EDX has the buffer that is encoded. The resulting string is also what I see in the outgoing web request.

If I continue, it hits 0x401d90, with the third arg being the response body from the server:

Continuing, this will crash, as it’s not valid base64 data, but I know in the PCAP response that’s what the body of the response was, so this makes sense.

MD5

I’ll put a similar break point at 0x403910, and (after disabling the other break points) run to it. Ghidra shows this one without a calling convention, so I’ll set x32dbg back to “Default (stdcall)”. The first arg is the string “FO927893”:

On running to return, EAX is now the hash of that string:

$ echo -n "FO927893" | iconv -f ascii -t utf-16le | md5sum

20786863fa9f1d3640556cfd21cf032e -

I have to use iconv to convert it to a long string before hashing it to get it to match.

I’ll also note that on running this through, 27893 is the number that shows up in the user agent string.

RC4

This paper does a nice job of going into the details of how RC4 works. Basically, there’s a KSA function, which initialized a 256 byte vector in a pseudorandom manner using the key. Then PRGA function uses that initialized vector to generate a stream of pseudorandom bytes that can be XORed against the plaintext to get ciphertext. That same stream (easily generated by anyone with the key) can be used to decrypt.

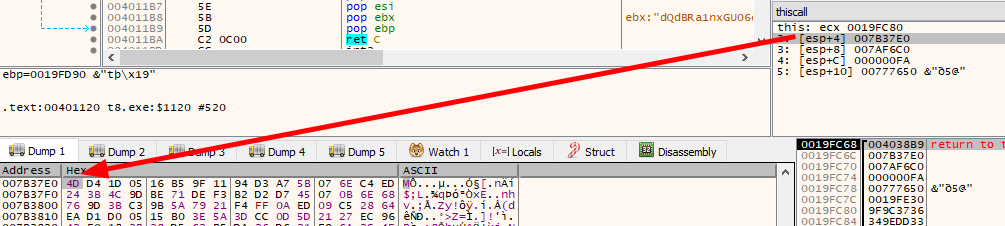

I’ll add breaks at both RC4 functions. The first to be hit is 0x4011c0, the KSA function. Ghidra shows this function as this-call, so I’ll switch x32dbg, and look at the second arg, which is the long hash string:

Some debugging will show that this hash is the same one I calculated earlier from the “FO9[num]” string, and that it changes each run.

Continuing on, the break at 0x401120 is hit. This one has an arg, “ahoy”:

If I continue on, in WireShark I’ll see the request:

I can throw that into CyberChef and it decrypts to “ahoy”!

Fail on PCAP Data

With that information, I’ll try to apply it to the PCAP data. The number is 11950, so the hash/key is a5c6993299429aa7b900211d4a279848:

It works for the “ahoy”:

But the response data isn’t anything meaningful:

Fake the Server

Setup

Strategy

I need to look at what the server does with this response. I do know from above that it attempts to base64-decode it, but then it crashed because the live server isn’t sending back base64 data. I’ll configure my network such that it connects to my server instead of flare-on.com, and send back data I can look at.

Configuration

I’ll edit the C:\Windows\System32\drivers\etc\hosts in my Windows VM so that flare-on.com is a system under my control:

10.2.23.101 flare-on.com

I could do localhost, but it’s a bit simpler to serve from a Linux machine and I’ve got one on the same network. When I run the VM now, there’s a connection at my machine:

$ nc -lnvp 80

Listening on 0.0.0.0 80

Connection received on 10.2.23.102 51322

POST / HTTP/1.1

Connection: Keep-Alive

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 7.0; Windows NT 6.2; WOW64; Trident/7.0; .NET4.0C; .NET4.0E; .NET CLR 2.0.50727; .NET CLR 3.0.30729; .NET CLR 3.5.30729; 29165)

Content-Length: 24

Host: flare-on.com

h60qaQOXkpg=

It hangs here waiting on a response.

Send Base64 from PCAP

Track Data into Decryption

I’ll fake the response from the PCAP using nc still:

oxdf@hacky$ echo -en "HTTP/1.0 200 OK

Server: Apache On 9

Date: Tue, 14 Jun 2022 16:14:36

TdQdBRa1nxGU06dbB27E7SQ7TJ2+cd7zstLXRQcLbmh2nTvDm1p5IfT/Cu0JxShk6tHQBRWwPlo9zA1dISfslkLgGDs41WK12ibWIflqLE4Yq3OYIEnLNjwVHrjL2U4Lu3ms+HQc4nfMWXPgcOHb4fhokk93/AJd5GTuC5z+4YsmgRh1Z90yinLBKB+fmGUyagT6gon/KHmJdvAOQ8nAnl8K/0XG+8zYQbZRwgY6tHvvpfyn9OXCyuct5/cOi8KWgALvVHQWafrp8qB/JtT+t5zmnezQlp3zPL4sj2CJfcUTK5copbZCyHexVD4jJN+LezJEtrDXP1DJNg==" | nc -lnvp 80

Listening on 0.0.0.0 80

Connection received on 10.2.23.102 51323

POST / HTTP/1.1

Connection: Keep-Alive

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 7.0; Windows NT 6.2; WOW64; Trident/7.0; .NET4.0C; .NET4.0E; .NET CLR 2.0.50727; .NET CLR 3.0.30729; .NET CLR 3.5.30729; 16315)

Content-Length: 24

Host: flare-on.com

qFjDfeHcg5A=

The program hangs where it gets here because neither nc nor the binary have closed the connection. I’ll Ctrl-c in nc to end it.

With the break point on both RC4 functions, it first hits the KSA one. I’ll note that the MD5 is the same as the hash used to encrypt “ahoy”. That means that the data I showed above is likely right, even if not meaningful.

At the PRGA function, it is trying to decrypt. The buffer in the second argument looks like this:

That matches what the data I sent decodes to:

$ echo "TdQdBRa1nxGU06dbB27E7SQ7TJ2+cd7zstLXRQcLbmh2nTvDm1p5IfT/Cu0JxShk6tHQBRWwPlo9zA1dISfslkLgGDs41WK12ibWIflqLE4Yq3OYIEnLNjwVHrjL2U4Lu3ms+HQc4nfMWXPgcOHb4fhokk93/AJd5GTuC5z+4YsmgRh1Z90yinLBKB+fmGUyagT6gon/KHmJdvAOQ8nAnl8K/0XG+8zYQbZRwgY6tHvvpfyn9OXCyuct5/cOi8KWgALvVHQWafrp8qB/JtT+t5zmnezQlp3zPL4sj2CJfcUTK5copbZCyHexVD4jJN+LezJEtrDXP1DJNg==" | base64 -d | xxd

00000000: 4dd4 1d05 16b5 9f11 94d3 a75b 076e c4ed M..........[.n..

00000010: 243b 4c9d be71 def3 b2d2 d745 070b 6e68 $;L..q.....E..nh

00000020: 769d 3bc3 9b5a 7921 f4ff 0aed 09c5 2864 v.;..Zy!......(d

00000030: ead1 d005 15b0 3e5a 3dcc 0d5d 2127 ec96 ......>Z=..]!'..

00000040: 42e0 183b 38d5 62b5 da26 d621 f96a 2c4e B..;8.b..&.!.j,N

00000050: 18ab 7398 2049 cb36 3c15 1eb8 cbd9 4e0b ..s. I.6<.....N.

00000060: bb79 acf8 741c e277 cc59 73e0 70e1 dbe1 .y..t..w.Ys.p...

00000070: f868 924f 77fc 025d e464 ee0b 9cfe e18b .h.Ow..].d......

00000080: 2681 1875 67dd 328a 72c1 281f 9f98 6532 &..ug.2.r.(...e2

00000090: 6a04 fa82 89ff 2879 8976 f00e 43c9 c09e j.....(y.v..C...

000000a0: 5f0a ff45 c6fb ccd8 41b6 51c2 063a b47b _..E....A.Q..:.{

000000b0: efa5 fca7 f4e5 c2ca e72d e7f7 0e8b c296 .........-......

000000c0: 8002 ef54 7416 69fa e9f2 a07f 26d4 feb7 ...Tt.i.....&...

000000d0: 9ce6 9dec d096 9df3 3cbe 2c8f 6089 7dc5 ........<.,.`.}.

000000e0: 132b 9728 a5b6 42c8 77b1 543e 2324 df8b .+.(..B.w.T>#$..

000000f0: 7b32 44b6 b0d7 3f50 c936 {2D...?P.6

This is a good sign that the data I want to decrypt has been sent for decryption.

Fix Key

Before continuing, right now it will decrypt with whatever string comes out from the timestamp at start up. But I want the hash to be the one calculated above, a5c6993299429aa7b900211d4a279848.

I’ll run again, (resetting nc each time), and this time when it hits the KSA, I’ll view the key in the dump:

After selecting the entire thing, I’ll right click and go to Binary -> Edit:

In the resulting window, I’ll paste the hash into the UNICODE field, and the hex view looks correct:

On clicking OK, the modified values are red in the dump:

Now, for the next RC4 run, it will be using this key and not the one generated for this execution. I’ll continue and it hits the break point at the PRGA. The second arg is the input data, and the third arg is the buffer to decrypt into:

I’ll watch the output buffer and run to the end of the function. The output matches what I got manually with CyberChef above:

Get Flag

Orient

Now that it’s about to return from the RC4 decryption, I need to understand where it is in the program. The Call Stack tab shows that:

FUN_403860 (which contains 0x4038b9) is one that takes a key, and calls bot hthe KSA and PRGA:

I’ve seen this function called during encryption as well. I need to go up further.

FUN_4043f0 (which contains the return to 0x40449b) is a relatively short function. FUN_403860 is called via the function table described earlier:

Up the stack one more is FUN_404200. This is where I’ll focus.

FUN_404200

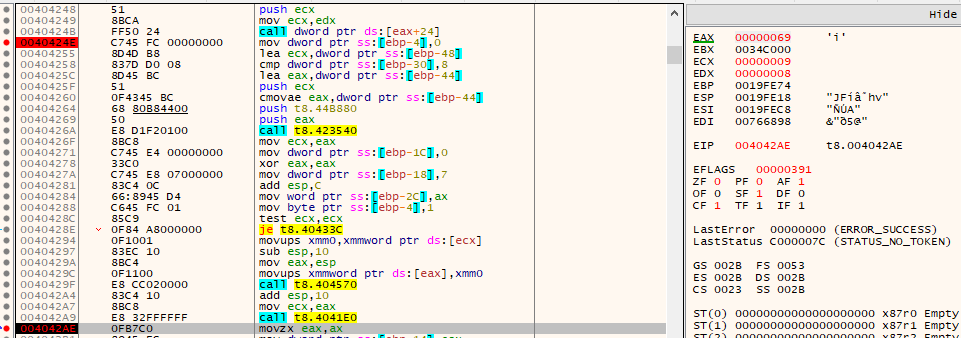

I’ll put a breakpoint at 0x40424e, which is the return from this set of calls. It’s just after a call to another function table function. While the decompile continues to not be great, I can get a high level idea of what’s going on from it:

After the function, something is passed to _wcstok_s, and then there’s a while loop until the token is null. _wcstok_s is a kind of split function, which will break a string on a given delimiter a given number of times, and return the tokens one at a time. The first call I pass in the string, and on subsequent calls I pass in NULL and it works from the same string.

I’ll notice that it’s splitting on “,”. I’ll also notice that it’s calling the function I’ve labeled time_calc, which is the same function that had to be 0xf to not sleep for half a day! The function immediately after I’ve named ith_letter (0x4041e0):

wchar_t __fastcall ith_letter(int param_1)

{

if (param_1 < 0x1b) {

return L" abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz"[param_1];

}

return L" abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz"[param_1 + 1];

}

I’ll add a break point a the return from ith_letter, 0x4042ae, and run to it:

EAX is the letter “i”. Knowing it’s a while loop and there are more tokens, I’ll run continue, and now it’s a “_”:

Next comes “s”, then “3”. Stepping through the loop a bit, the new letter is appended to a buffer in a memcpy call at 0x4042f7.

Continuing ahead, eventually the full flag is constructed at 404AA1, where a function call appends the “flare-on.com”, and the flag is in the return (EAX):

Flag: i_s33_you_m00n@flare-on.com

Click for full size image

Click for full size image Click for full size image

Click for full size image Click for full size image

Click for full size image Click for full size image

Click for full size image Click for full size image

Click for full size image Click for full size image

Click for full size image Click for full size image

Click for full size image Click for full size image

Click for full size image Click for full size image

Click for full size image Click for full size image

Click for full size image